. . . LAND ROVER OVERLAND EXPEDITION

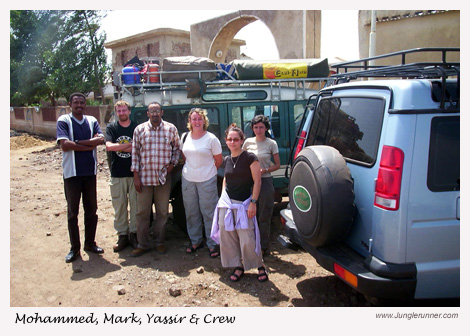

#10 - Across the Sahara (Sudan) (Aswan, EGYPT) - Entering Sudan from the south was a challenge of mud, long stretches of decent dirt road interrupted by swampy troughs that needed to be scouted, analyzed, and then attacked. Failure was a hassle, an hour of digging or getting pulled out by passing trucks, but no more than that. However, heading north from Khartoum on our way to Egypt we met the eastern edge of the great Sahara. Getting stuck meant a whole different magnitude of trouble, we were an insignificant dot in the barren sea of sand, there would be no help. We were playing for higher stakes, survival. An hour into the desert the truck began to bog down, we were carrying too much weight and the wheels were breaking through the crust of the sand. Downshifting frantically I kept the engine revs as high as possible in order not to stall, fourth, third, second, first gear � we churned through the soft sand and regained firmer traction. The first time it happened I was concerned, but soon we were bogging down regularly and an edge of terror crept into my gut. How different from the euphoria one week earlier. After crossing the "impossible" section of road from the border of Ethiopia to Gedaref, Sudan where the paved road starts � we were riding high. We blazed through town in the dusk planning to charge on directly to Khartoum. We'd been warned that visitors must register at the police station in every town where they stay overnight. It was also necessary to get a travel permit to transit the country � more long waits, more bureaucratic fees. Why not drive all night and arrive at Khartoum saving the hassle of registration we thought. But as we hit the edge of Gedaref, a brand new Land Rover Discovery pulled up behind us and began flashing its lights emphatically. What now? Two beaming Sudanese guys leaned out of the truck, "We are from Nefeidi Motors, the new Land Rover dealer in Sudan! You must stay with us for the night in Gedaref." "No thank you, no problem, we are just driving to Khartoum." "Impossible," Mohammed replied emphatically, "you will stay at our hotel and then we will all drive together to Khartoum tomorrow!" It was our first taste of Sudanese generosity.

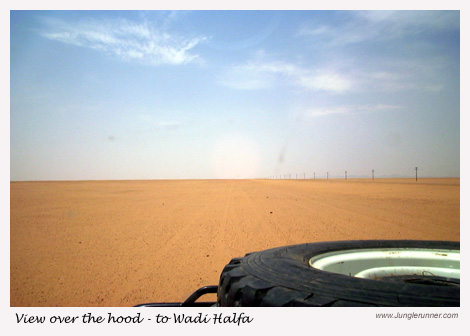

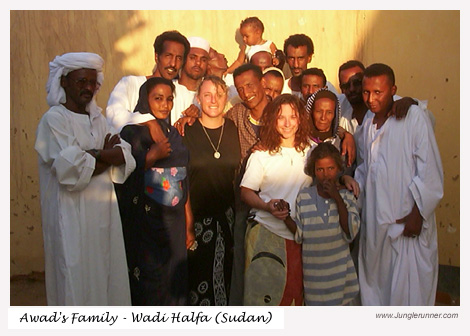

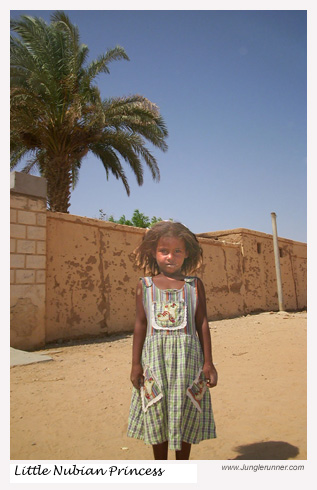

They insisted on waiting another three hours with us at the station, installing Sally and Jody in their Discovery for the five hour drive to Khartoum (our A/C had quit and the outside temp was 110 degrees), taking us to their parent's house for dinner, finding us a suitable hotel downtown. We continuously demurred, please, it's no problem, we can manage by ourselves. "Of course not! It is our pleasure!" they would reply. Yassir personally took me to the Land Rover garage the next day and arranged for a shop discount. They drove us around town, took us swimming at a private club, bought us ice cream, and finally after days of generosity when we were determined to continue north they convinced us to sleep one last night under the stars on the rooftop terrace of Yassir's parent's house. It was a good opportunity to find out more about Sudan. How could a country with such amazing people have such a terrible reputation in the west? "We are Muslim" Yassir said simply. "We are fighting against the rebels in the south who want to break up the country." "They are Christian aren't they, do you think that the west identifies with them more?" "Maybe, but to say that the rebels are one group with a clear agenda is not to understand the reality of Sudan. There are many groups fighting, each of them wants their own things." "What about the slavery going on," I asked delicately � not wanting to be rude. "It happens" Yassir answered straightforwardly, "but almost all of it happens in the south, one group captures children from another and sells them to finance their war. This country needs a strong central government, without it the south would be anarchy like Somalia." I laughed, "OK fine, but you don't have a democratically elected government � it's a military junta." "True" replied Yassir, "but each young man must serve one year in the military and this let's them feel like they are part of the government. At least now there are rules for doing things. In the past there was no legislation for anything. The government did what it felt like. We need to have rules so that companies can do business here." "Still," I mused, "this country is set up like Nigeria. You have developed oil fields and a couple of significant new discoveries just announced. What is to stop a couple of top military brass from stealing most of the wealth?" "Ahhh, that is the problem isn't it", Yassir shook his head then perked up, "More coffee?" Yassir and Mohammed represent a small elite in Sudanese society. Muslim Arabs, a tiny minority in the overall population, control most of the senior posts in the military and business. Their company, Nefeidi Motors, is one fourth of the Nefeidi Transport Group, which is fully owned by the SMC conglomerate � the few control the most. Yet even in a relatively privileged class, Yassir still longs to emigrate. As he told me one afternoon, "No matter who you are, Sudanese life is like the army � hard." Even its countryside is measured in extremes, Sudan is the largest landmass in Africa but most of the land is sparsely settled desert, with a fringe of rainforest on the southern edge. The capital of Khartoum is situated at the confluence of the White Nile (coming north from Lake Victoria in Uganda) and Blue Nile (flowing west from the highlands of Ethiopia). The combined Nile flows north nourishing Nubian fishing villages in the parched landscape. We had longed to escape the cold and rain of Ethiopia, but a few hours of mind-numbing Sudanese heat had us changing our minds. In Sudan they like their women to have some meat on their bones, and with her blonde hair and light eyes, I started calling Sally the Sudanese supermodel. One of the perks of traveling with women is that we got special attention wherever we went. So it was disappointing but not totally unexpected when Yassir and Mohammed sullied their reputations a bit by making passes at Jody and Sally on the last night. Boys will be boys and foreign women have a reputation for being "loose", but it was still a bit bitter after such a sweet stay. In Khartoum we spent the first night at a campsite on the banks of the Nile because the prices at the hotels were outrageous. Normally there would be a few bargain hotels in such an untouristed country, but because of the new oil field discoveries the hotels are full of expatriates. Though the campsite price was right, the Nile mosquitoes are so small they can crawl right through the tent screens (and closing the flap isn't an option in the sweltering night) � so one sleepless night of a thousand bites convinced us we needed to spring for an A/C room. A further problem in Sudan is the lack of any credit card facilities or cash advances � there isn't even a Western Union here, so we had to preserve our precious stash of cash to make sure we had enough to pay for the car ferry to Egypt. We thought Ethiopia had no tourist infrastructure, but Sudan hit new lows. The consolation was Sudanese food, the mix of beans, fish, bread, and imported Middle East cuisine was a welcome relief. On Sunday we headed north, intending to check out the ancient Nubian capital of Meroe on our way. But a complete lack of signs (and my male reluctance to ask for directions) left us mystified as to the location, and in the end we completely missed the city � a shame because it is about the only serious tourist draw in the whole country. The fine paved road gradually petered out and by the time we reached the town of Berber we were on a gravel track. Filling up with diesel at the battered two-pump station, scorching hot in the 110 degree heat, we asked about the road. "Follow the train tracks!" the villagers directed. "Up to Abu Hamed the train runs beside the Nile. Stay on the right side the whole way." Easier said than done. This year the rains were particularly strong and the Nile is at its highest level in recent history. As we bumped along the gravel track through black volcanic foothills and sand covered depressions, the river occasionally swallowed up the road. Fording was not an option in the waterlogged sand, we tried once, got stuck, and took an hour to dig out. The only way around was to scramble cross-country finding our own track in the desert until we found solid ground. Occasionally while wandering we'd lose sight of the river and a wee dash of panic would set in until we got re-oriented. Villages were very sparse and only located on the banks of the Nile. A few miles inland and there would be no help if we got in a jam. Though I'd bought maps for the full length of the trip, their accuracy had proven to be a bit dubious � oh for a high quality GPS! At dusk we camped next to two mud huts after asking permission. The old grandfather was amazed at our folding camp chairs and tents, and wandered down to watch from up close. "Ayeh mufliga fungh befuutu" he said earnestly (no that's not Nubian � it's just what he sounded like). "Ahh, yes!" we said. And so it went for an hour. He felt compelled to comment on our entire camping process � and especially liked chatting with Jody. "I don't know what you are saying!" she would laugh. "Yes. Yes." he'd reply. From Berber it was 260km of twisting gravel road and flood induced detours to Abu Hamed � the start of the Sahara. A few kilometers before the city I slowed a bit too much during a detour and the truck bogged down in a very innocent looking patch of sand. We pulled out the sand ladders and the truck came right out � but bogged immediately. Re-inserted the ladders, out and bogged. Again. Finally, on the fourth try the front wheels found some rocky ground. Later, when we pulled into Abu Hamed we stopped at a merchant compound at the edge of town hoping to find a 5-ton lorry with whom we could convoy � and got stuck again. This time it took fifteen people pushing to pop us out. By the time we set off on the last 400km stretch of desert, I knew it would be disastrous to slow or stop in any sand. One strange thing about driving in the desert is the lack of a marked road, tracks spread out half a kilometer in width, each vehicle seeking the hard crust of unbroken sand. To maintain momentum we drove 80kph, which led to my second discovery � the desert isn't a velvety smooth expanse of sand. A long stretch of level ground would suddenly be cut through by wind-eroded ridges a foot high. An hour out of town the sand began to soften, the truck labored to maintain 80kph and the temperature gauge began flirting dangerously with the red zone. "No more A/C" I said regretfully, the women groaned. We sat in the truck, windows down, a hot windblast sandpapering our faces, sweating like convicts. The rail track was my security blanket, the only definite solid ground, but terrain or truck tracks would force me to veer one or two kilometers away � each time I would anxiously search for a way back. Coming over a ridge I smacked into a series of deep washouts without warning, the truck hammered into the washout, bucked into the air and hit the second even harder. Everything flew forward, 20 liters of bottled water, backpacks, and bundles, Sally and Jody were assaulted by the barrage. "Stop Jeff. Stop the truck!" Sally yelled at me. "If I stop we will be screwed" I shot back through gritted teeth. We drove on, Gulin staring ahead numbly in the front seat, rivulets of sweat streaming off her forehead. Jody was huddled in the rear seat gripping her leg, crying softly � she had dislocated her knee. After half an hour Sally said softly, "Jeff, we really need to stop." Driving over to the rail track, I mounted the two-foot high embankment and bounced along the rail ties. We stopped to strap up Jody's knee. "I'm sorry about the bumps, but do you understand that I am terrified right now" I said quietly. With all diesel tanks full, water tanks, drinking water, food, and baggage, we were too heavy. If we bogged down we'd never get back on top of the sand till we hit solid ground. If we bogged down fifty meters from the rail track, our sand ladders would only take us three meters at a time, and it would take us hours to dig our way back to the track. If we got caught a kilometer away, it would take days. In 400km we passed no vehicles and saw no human being. We were alone. To their credit, the women all understood and absorbed the punishment. And so it was that the worst, most dreaded section of the Cape to Cairo route was conquered, in rainy season, by the spirit of human kindness. The Land Rover undercarriage paid a steep price, shakes and rattles would have to be fixed in Khartoum � but we had not been stuck for a week in the rain, digging for hours and hours as others had promised. We did the worst section in only five hours, and Mark said, �Alright.� Through the worst of the afternoon heat, for six harrowing hours, we plowed through the desert. Occasionally the track was so bad that I just drove on the rail track bed, our teeth chattering as we rattled across the rail ties. Finally in the distance, Lake Aswan glimmered, we stared to be sure it wasn't another mirage. Wearily, I steered off the rail track and we limped into the town. Seldom have I been so tired. Worn out and dusty from the heat, exhausted from the knot of fear in my stomach, arms aching from the pounding. "I'll have nightmares about this day," I said to Sally � and I did for the next couple of nights. Wadi Halfa was a prosperous border town before the High Dam was constructed in Aswan, Egypt. In 1964 the town was flooded along with most of the traditional homeland of the river dwelling Nubian population by the rising waters of Lake Nasser � the worlds largest man-made lake. We arrived to a cluster of tattered tin shacks, some of which had Hotel written on crude signs. No A/C, no showers, just a foam mat in the courtyard and a bucket. Again, Sudanese hospitality saved us. Awad, a tall, lanky, soft-spoken businessman saw our dilemma. "Please, you must come and stay at my house." "No, no, we are ok", my Canadian reserve obliged me to say. Gulin turned to me, "Jeff, sometimes you have to accept the kindness of strangers!" And so it was that we stayed with Awad and his incredibly gracious family for a week while we waited for the car ferry to take us to Egypt. We slipped into the rhythm of the sleepy backwater town; sleep outside in the courtyard, wake at 8am for sweet tea with milk, breakfast at 11, lie inside in the shade panting in the 120 degree heat, sweet tea without milk at 1pm to make sure you sweat, lunch at 4pm, tea with milk at 6pm, finally the blessed chance to take a bucket bath with cold water, dancing at a Nubian wedding (they seemed to have one every night), and dinner at 11pm in the cool evening. Though the wait was frustrating, each day the little village grew on us. One night Gulin went out for a walk and was spotted going toward a section of desert notorious for hyenas � 20 men turned out to carefully follow her tracks, following her wanderings till she was found safely. Another time Jody needed an IV to re-hydrate after a nasty stomach bug caused her to throw up all day, and dozens of people stopped into her hospital room to check on her in the course of a couple of hours. Though the civilization of Egypt beckoned like a siren, we were really sad to say goodbye to our adopted family as we loaded the truck onto the cargo ship for the two-day voyage to Egypt. Sudan is a tough country to navigate, but like a desert melon, the tough exterior hides true sweetness inside.

|

All rights reserved