. . . LAND ROVER OVERLAND EXPEDITION

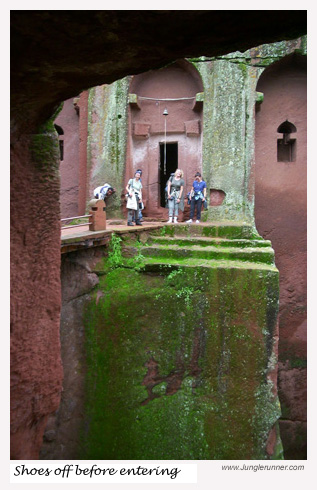

#9 - Ethiopia to Sudan (Khartoum, SUDAN) � I�ve already written enough about the trials of Ethiopia. Unfortunately the best sights in the country are undermined by a spectacular lack of decent hotels or restaurants � even high-end facilities struggle to offer decent hospitality. We took a UK-based aid worker out to dinner at the nicest hotel in Gondor and remarked on the appalling food. �It�s not that they don�t care� she commented, �I�m convinced they are just terrible business people.� Despite its deprivations, Ethiopia still has a lot to recommend it. If you�ve ever wished to see a truly world-class sight, something unspoiled by Western �improvements� to sanitize it and lawsuit-proof it � then you have a rare opportunity. One of the oldest hominid skeletons, �Lucy�, was discovered in northern Ethiopia, earning the �cradle of humanity� title for the country. Ethiopia also boasts the longest record of civilization, longer even than ancient Egypt, stretching back over 5000 years. In the north, the ancient city of Aksum served as Ethiopia�s capital for millennia. Sitting astride the key trading routes, it profited from the export of ivory, gold, and slaves to the Red Sea countries and beyond � it�s record of glory is preserved in gigantic carved stele, the last of which was the largest piece of carved stone ever produced in the world. Aksum declined over time as empires tend to do, but around the time that Christianity took root the capital moved to Lalibela. There, religious kings commissioned a series of remarkable churches. Carved into soft lava rock, the structures are all below the surface of the ground � carved in their entirety, floor, walls, and roof, from solid stone. Several hundred years later, forced to abandon Lalibe la by the Moorish expansion in the north, the government existed for centuries in a gigantic traveling camp. But early in the 14th century a new capital city was constructed in Gondor. A series of castles were erected by successive kings that rival the best of that period in France or England � it was the Renaissance of the country. Emissaries from Portugal described one of the king�s palaces as opulently decorated with gold, ivory, and sumptuous tapestries, warmed by a series of internal fireplaces.

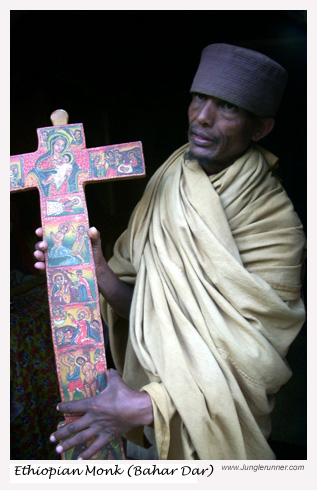

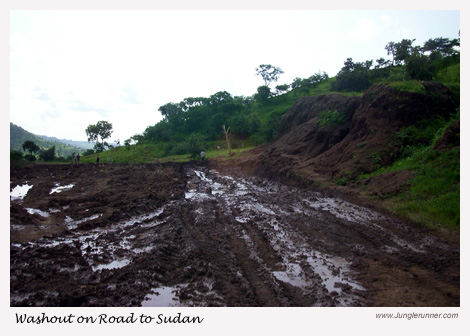

Coptic Christianity remained a vital faith, and the crown supported a dozen monasteries on nearby Lake Tana. Accessible by boat from Bahar Dar, the monks remain, proudly showing ornate brass and silver crosses, centuries-old goat-skin manuscripts of the Bible written in Ge�ez, and the unique painting style on the icons and monastery walls. During the European scramble for Africa, Ethiopia was never colonized, the only country in the continent that remained independent. Prior to WWII, Mussolini invaded the country on a massive scale, intending to secure his own African colony. But the price of occupation was high. Crude weapons, patriotic fervor, and the mountainous terrain cost the Italians terrible casualties. After a few years they were able to take the major cities, but the countryside was never subdued � and at the end of WWII Italy was forced to cease its occupation. Our tour north of Addis Ababa to Lalibela, Bahar Dar, and Gondor took a week. If you book a package tour paid in advance, take lots of $US cash, and expect little from the hotel food despite the prices � then you won�t be disappointed. In the constellation of �places you must see�, Ethiopia is too important in world history to be ignored, and you have a chance to see the sites in their natural state at present. Though there are only four on the Junglerunner crew, we seem to constantly travel with five. First Devy and Rob in southern Africa, then Sally�s boyfriend Mike joined us for three weeks. In Addis we met up with a young Slovak Count, Viktor (last name withheld by request). Educated in the finest English prep schools (what, what) he was an interesting addition to the team and often had a different perspective on things. On the unrelenting misery of kids badgering us with their two words of English, �You� and �Money�, he commented, �I wonder if one could acquire a permit to export urchins by the kilo. They seem to have quite a surplus here.� Despite the caustic comments he was thoroughly likeable. Dark comedy seemed the only way to deal with the strain as one by one the crew went mildly insane. As we left Gondor we bid adieu to Viktor, only to pick up Mark, a slight, bearded, Penn State Psych grad who had been trying to hitch a ride to Sudan for days and seemed to be almost at the end of his rope. Mark�s comments were much more condensed than Viktor�s, his favorite saying was, ��. Or sometimes he would say, �Yes.� Or maybe, �No.� For all that, we were still happy to have him along. Passing 4x4s had updated us on the condition of the road into Sudan, it was terrible. One couple had taken four days to cover 100km � getting stuck twenty times. It looked like we would be in for a rough time. Song of the Children � an Ethiopian Haiku For the first time on the trip, I got out to reconnoiter. From Gondor to the Ethiopian border was supposed to be all good road except for a couple of kilometers � but the 100m stretch of axle-deep ruts awash in knee-deep muck looked impassible. I left for the border driving with an icy stomach. Few things unnerve me like getting hopelessly stuck. Growing up in Congo, I know that the difference between scrambling through a washout or getting so stuck that it will take half a day of hard digging is often differentiated by a few inches mis-steered or a few km off-speed. Wading through the mud in my Teva sandals, I was resigned to spending several hours filling in the ruts from the hillside. A good way to test the depth of murky puddles is to throw in stones, though this has the downside of getting you covered in muddy splatter. Already coated in filth, I decided I had nothing to lose, and started chucking rocks. Hmmm. The puddle was shallower than it appeared. It might be possible to straddle the rut initially, then dodge left dropping the driver-side wheels eighteen inches into the muck, scraping the side doors on the bank, and power out with diff lock, low gear, and just the right amount of speed. Everyone piled out, I sloshed off the worst of the muck from my sandals (it can be disastrous if you slip off the clutch or gas at the wrong time just because the pedals are coated in mud), and powered through the sludge pit. Whew. One down, many to go. We made the border just as night was falling. A few anxious moments, but never did get stuck. Both Ethiopia and Sudan are improving their respective sections of road at the Metema crossing. It will be the primary conduit for cheap Sudanese oil going to Ethiopia and Kenya. For the past decade, this section had been the chokepoint stopping overlanders from attempting the Cape to Cairo run. In a year it will be a breeze � but that is small consolation today, and to make matters almost impossible we are attempting the crossing in rainy season. We camped in a cluster of mud huts that comprised the Ethiopian border post. A last night eating sour injera on rickety seats in a thatch roofed hut � after nineteen days of unrelenting injera or spaghetti, all romantic notions of blissful national cuisine are long gone. Jody and Sally slept in the roof tent, Mark pitched the tent on the muddy ground, while Gulin and I slept on the interior deck inside the truck. We�d dropped thousands of feet in altitude and the cold rainy weather had given way to oppressive heat. With the windows closed we managed to keep the mosquitoes out, but the cabin soon doubled as an oven. Finally I gave up and opened up the rear door, letting the mosquitoes fly in at will. Not much sleep that night. Sudan has no facility to obtain outside money � not even Western Union. We were forced to get one more cash infusion in Ethiopia before crossing over (since we were not in the capitol the conversion rate was 13% lower), and to add insult to injury we then had to convert the Ethiopian Birr to Sudanese Dinar prior to crossing. It is illegal (and jailable) to do �informal� currency exchange in Sudan and the Sudan bank won�t convert Ethiopian Birr. The net result of this four-step process was a rate of 220 Dinar/$1 � instead of the bank 260 Dinar/$1. It doesn�t matter. We long ago stopped fretting about conversion fees and bank rates. Without cash for diesel and essentials our trip is over. Entering Sudan was a painfully slow process. They don�t get many tourists here and it shows. Passports and Carnet documents were passed around from person to person in the mud block office and examined with thoughtful scrutiny. Papers were written out in triplicate. Customs took an hour. At the Immigration hut we sat for half an hour on a bed while the officer finished his breakfast. He filled out the forms and took them to another hut where we sat again for twenty minutes watching that group finish their lunch. Through it all I felt no urgency. It was like waiting for a shot in the doctor�s office, any delay is ok. I wasn�t looking forward to the driving hell that was to come. Finally on the road. Glory be, it hadn�t rained in four days and the ground had dried out somewhat. It was a little thing, but it made all the difference. Long sections of axle-deep mud were ground out with differential lock and wild slaloming. Washouts had edges just dry enough to support a crab like straddle, wheels spinning at high revs to cling to the edges and avoid sliding irretrievably sideways. We were able to drive through farm fields to avoid the completely impossible sections � where stranded five-ton trucks were stuck, tilted over like abandoned shipwrecks in a sea of black rutted waves. The Land Cruiser asked if they could convoy with us and we agreed. We plowed through mud and washouts together till we reached another impossible section. The Land Cruiser tried a side route, but it was blocked by a white 4x4 pitched down so far that the top of the hood was under mud. In the meantime, I stayed on the main road, watching a 5-ton Bedford lorry trying to struggle through the main section. A 5-ton lorry is the nemesis of a 4x4. It�s tires are huge, and the track width a foot wider. Once a couple of lorries have dug out ruts, a 4x4 can�t pass. It must either straddle the edges, try to blast through (dragging the axles and transmission through the dirt in the process), or go around. �Do unto others as you would have them do unto you� is the Golden Rule. I pulled out the towrope and handed it to the surprised driver of the lorry � �let�s dance.� With low gear on solid ground the Land Rover has amazing pulling power and I jerked the brute right out of the pit. No sooner had we cleared than a second lorry plowed into the washout and got stuck. Round Two � Bam, pulled him right out of there. And so it was that the worst, most dreaded section of the Cape to Cairo route was conquered, in rainy season, by the spirit of human kindness. The Land Rover undercarriage paid a steep price, shakes and rattles would have to be fixed in Khartoum � but we had not been stuck for a week in the rain, digging for hours and hours as others had promised. We did the worst section in only five hours, and Mark said, �Alright.�

|

All rights reserved

In

fact, after we had crossed the halfway point we started to relax.

We tag-teamed with a Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up for a while gaining

confidence that we could power through the worst of it. The pick-up

turned off, waving good luck as they went, and we started feeling

cocky. But the two worst tests were yet to come. Around a corner

in a village we slowed and halted, a twenty-foot lake blocked the

road. Normally we would have forded it, but a huge crowd had formed

near the roadside and three vehicles were in various immovable states.

No, no! the crowd motioned, don�t try the water, go around. It was

a serious barrier. A thorn goat pen hedged in one side of the narrow

lake verge, mud was really deep and slippery, and to make matters

worse a stranded Land Cruiser blocked the exit point. We would have

to blast in, turn left, and climb a two-foot dirt wall in order to

get around. I tried. I failed. Stuck in the mud with the front wheel

perched on the wall, I couldn�t go any further. In an amazing scene,

the crowd swarmed around, �Do you have a rope?� I pulled out our

towrope, they fastened it on the front bumper, and thirty men grabbed

it in unison, heaving the truck up and over the wall. We�d been told

that the people in Sudan were some of the friendliest in Africa,

and we were just seeing the start of it.

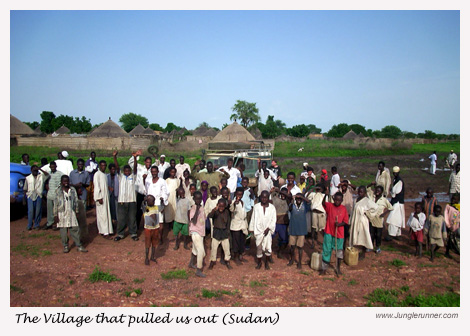

In

fact, after we had crossed the halfway point we started to relax.

We tag-teamed with a Toyota Land Cruiser pick-up for a while gaining

confidence that we could power through the worst of it. The pick-up

turned off, waving good luck as they went, and we started feeling

cocky. But the two worst tests were yet to come. Around a corner

in a village we slowed and halted, a twenty-foot lake blocked the

road. Normally we would have forded it, but a huge crowd had formed

near the roadside and three vehicles were in various immovable states.

No, no! the crowd motioned, don�t try the water, go around. It was

a serious barrier. A thorn goat pen hedged in one side of the narrow

lake verge, mud was really deep and slippery, and to make matters

worse a stranded Land Cruiser blocked the exit point. We would have

to blast in, turn left, and climb a two-foot dirt wall in order to

get around. I tried. I failed. Stuck in the mud with the front wheel

perched on the wall, I couldn�t go any further. In an amazing scene,

the crowd swarmed around, �Do you have a rope?� I pulled out our

towrope, they fastened it on the front bumper, and thirty men grabbed

it in unison, heaving the truck up and over the wall. We�d been told

that the people in Sudan were some of the friendliest in Africa,

and we were just seeing the start of it. Most

lorries travel overloaded with cargo, with ten or twenty people clinging

to the top as paying passengers. As the two lorries started to take

off, the passengers began yelling at the drivers � �We wait till

they have made it through to the opposite side!� It was a daunting

washout, the tire ruts were a full three feet deep. Still, I gunned

the engine and tried to dance across straddling on the edges. Halfway

across I felt things go bad, the truck started sliding out and within

seconds had slipped left into the rut. I bogged down, irremovably

tilted at a thirty-degree angle, my window almost level with the

ground. It was a horrible feeling. Even forty people pulling on a

towrope could do nothing about this. But just at that moment, a massive

ten-wheeled dump truck thundered past, shouldering through the worst

of the washout (digging it out even worse as it went). And it was

then that the Golden Rule paid off. The crowd swarmed the truck,

yelling at the driver to stop and pull me out. He was reluctant but

they were persuasive. The giant yellow truck reversed into the swamp,

threw the rope around it�s axle, and flicked the Land Rover out almost

effortlessly. The crowd yelled and applauded. We high-fived. Sally

handed out cigarettes. It was one of those moments. We only got stuck

twice that day and both times we were rescued in impressive fashion.

We stayed with the Land Cruiser most of the way to Gedallat, helping

them get unstuck one more time, but the truck handled the rest of

the road with equanimity.

Most

lorries travel overloaded with cargo, with ten or twenty people clinging

to the top as paying passengers. As the two lorries started to take

off, the passengers began yelling at the drivers � �We wait till

they have made it through to the opposite side!� It was a daunting

washout, the tire ruts were a full three feet deep. Still, I gunned

the engine and tried to dance across straddling on the edges. Halfway

across I felt things go bad, the truck started sliding out and within

seconds had slipped left into the rut. I bogged down, irremovably

tilted at a thirty-degree angle, my window almost level with the

ground. It was a horrible feeling. Even forty people pulling on a

towrope could do nothing about this. But just at that moment, a massive

ten-wheeled dump truck thundered past, shouldering through the worst

of the washout (digging it out even worse as it went). And it was

then that the Golden Rule paid off. The crowd swarmed the truck,

yelling at the driver to stop and pull me out. He was reluctant but

they were persuasive. The giant yellow truck reversed into the swamp,

threw the rope around it�s axle, and flicked the Land Rover out almost

effortlessly. The crowd yelled and applauded. We high-fived. Sally

handed out cigarettes. It was one of those moments. We only got stuck

twice that day and both times we were rescued in impressive fashion.

We stayed with the Land Cruiser most of the way to Gedallat, helping

them get unstuck one more time, but the truck handled the rest of

the road with equanimity.