. . . LAND ROVER OVERLAND EXPEDITION

| Home | |

|

Journals

|

|

|

VALUED SPONSOR |

|

Into the Margins Sleeping inside a Land Rover in the middle of the

jungle can be unsafe. Doing it next to a town of unemployed desperados

is a stupid risk... Commercialism is insistent, creeping

into the cracks of indecision, sophisticated. To survive in the First

World we develop mechanisms to deal with the overwhelming quantity of

choices. If you want something on your bread you have to pick; jam, preserves,

nut spreads, Marmite, margarine, peanut butter, cream cheese, butter � and

then refine your choice; which brand, what size, low fat, low cal, squeezable,

plastic, glass. Think about it, when you pick Jif peanut butter

you�ve chosen from over a hundred different options, and if the store

is out of Jif you can make do with Skippy or Kraft. But on the ragged

edge of civilization, all the options are stripped away � suddenly you

are outside comfort zone� into the margin. I�d been coddled

by the southern Africa countries of my trip and shot into the guts of

the real Third World unprepared. The next three weeks were a struggle

just to keep going, to find food, shelter, petrol � the margin between

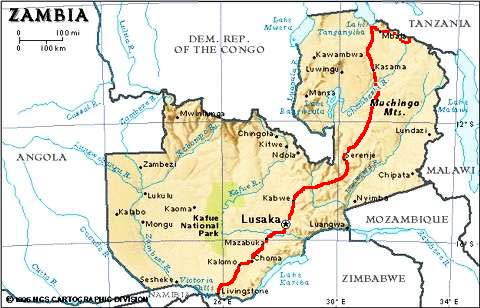

comfort and ruin. Zambia Zambia curls around the south-eastern

tip of Congo and is bordered by Angola to the west, Zimbabwe and Mozambique

to the south, and Malawi to the east. It's a relatively large country

of 752,615 sq km with a population of about 10 million - an unusually

low density for a developing country. Colonized as Northern Rhodesia

during the mad scramble at the beginning of the century, it received

far less infrastructure than Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) to the south - although

the copper mines in the northwest attracted special attention. It followed

a depressingly predictable course after independence - the copper mines

were nationalized, export income was siphoned, corruption flourished

and the infrastructure crumbled. Amazingly in 1990 the ruling party

with its resident Big Man lost in the elections. Even more amazingly,

he stepped down gracefully. The newly elected president Chiluba embarked

on a campaign to restore the country's fortunes - but had to accept some

bitter medicine in the process. Domestic spending was slashed to halt

inflation and the standard of living of the populace got worse not better.

After almost ten years in power, Chiluba seems to have turned the corner.

The mines were recently sold to a foreign consortium that promises to

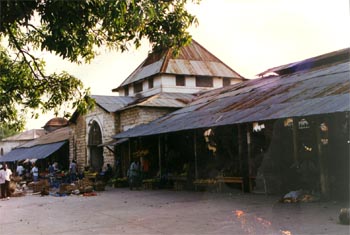

invest the requisite millions to make them profitable again. A market

economy has been restored and the IMF and World Bank have tangibly applauded

Chiluba with a package of loans that will hopefully increase the local

standard of living. I was stopped a dozen times at checkpoints

on the road, and each time was pleasantly surprised at the efficiency

and lack of bribe requests. In our conversations Richard had mentioned

that Chiluba recently appointed a Minister of Revenue from New Zealand

and replaced almost every senior manager with western replacements. Within

one month the amount of collected revenue tripled, testament to the crippling

effects of institutional corruption. Zambia is back on its way up � although

the jury is still out as to whether Chiluba will subject himself to free

and fair elections. Rough Reality There was a long way to go and a

highway newly paved with foreign aid, but the truck had developed a high-speed

vibration and couldn�t get past 100kph. A long expensive stop to

balance all four wheels made no difference, and by early afternoon the

road had degenerated into a bone crunching ordeal. I beat through

the heat of the day - the A/C quit working. Night finally dropped

its cool blanket. I siphoned the last of my petrol from the roof jerry

cans and gave my granola to a hungry guy who had stopped to watch. Beating

into the moonless night watching the gas gauge fall I started feeling

pretty vulnerable. Finally I reached Mpiki and a 24hr BP gas station,

thank goodness for capitalism. Gas stations are the leading economic

indicators in African, the first signs of a stirring economy are the

shiny BP or Shell stations in the middle of mud hut towns. The first Swahili I'd heard on the

trip, a safe brightly lit oasis and gas for my three tanks � I was so

happy that I filled everything. Belatedly I realized that I didn't

have enough Kwacha. "No we've never taken credit cards. No, traveller's

cheques aren't accepted in the country. No. No. Cash only." No banks,

no ATMs, no moneychangers, I�d been told to travel with lots of US cash

but southern Africa had lulled me. I'd dived into real Africa from

the vestiges of civilization and this was to be my induction into Survival. Noel Sikaumbwe, night attendant,

pondered my problem. Yes he would accept 20 litres back if I siphoned

them out of a jerry can. That left me owing 5,000 kwacha - $2.50. No

solution could be found. I tried selling some of my food to passing motorists.

Noel sympathised. Finally he offered to pay the remainder, a touching

gesture since 5,000 kwacha represented a week of his salary. Would I

like to park the truck and sleep at the station? I would. The

New African Class Noel cautioned me as I bedded down

in the Land Rover, "When the soldiers come, tell them you have talked

to the owner." At 2am there was shouting from the night patrol outside, "Hey,

hey you, wake up, what are you doing?! Get out of the truck. You're driving

where? All this way! Oh you are from Canada. Well drive safe." Mackson

the night guard was an inscrutable presence throughout the night. In the morning Noel and Mackson let

me sleep in till 5:30, then we shared tea. Mackson approached me gravely

and asked if I had a clean piece of paper - he had saved the tea bags

and would take them home to his wife. I gave him the package of 25. He

looked quite astonished and recovered to thank me solemnly. I gave Noel

a can of Milo, a box of cookies, and a box of granola bars � hopefully

he would be able to sell them for more than 5,000 kwatcha. We left

friends. Another six hours of bumping to arrive

at Mpulungu, the end of the road - literally. The road goes through the

tiny port and ends at Lake Tanganika, the lake of my youth. Seeing it

again jogged years of memories and I couldn't wait to take the boat to

Kalemie - my old home town. I was directed to the only campsite in town

and met Aseef, the camp owner. The boat wasn't coming till Friday, five

days away. No he didn't take travellers cheques but he could find a local

merchant who could exchange some for me. If I was going to Kalemie I

should talk with that woman there � she had just fled the fighting with

her family. Fighting?! I approached the woman and in halting Swahili

asked about Kalemie. "Oh you must not go, there is much trouble.

Yes there is fighting - many people have died." Change

of Plans I'd pushed hard to arrive in Nakonde

before 6pm in order to get across the border - the town had a reputation

as a wild border crossing with plenty of scams, crooks, thieves, and

killers. We made the town by 5:20 and tiredly but triumphantly I dropped

my passengers and went to the gate - closed - come back tomorrow. No

kwacha. Dangerous town. What to do? Noel had said that Zambia had no

history of internal violence, "We are a peaceful people." I

decided to head back into the country and make a jungle camp - preferring

natural dangers to manmade. 20km out I turned into the bush. Jungle

Camping Sleeping inside a Land Rover in the

middle of the jungle can be unsafe. Doing it next to a town of unemployed

desperados is a stupid risk, one that I had plenty of time to think about

as I scrunched sleepless in my metal and glass cocoon. I dreaded a sudden

face at the window in my peripheral vision. Midway through the moonless

night I thought I heard footsteps and felt numb with fear gripping my

pepper spray and American Tourister alarm. Blood pumped through my ears.

Fatigue finally overcame fear and I slept fitfully. Francis, one of the ragamuffins,

showed up the next morning and helped me consume my breakfast. As I re-tied

the roof-mounted jerry cans the soldiers arrived brandishing assault

rifles and I was hustled to the station. What was I doing? After my explanation

I was given a thorough lecture by the captain, "Next time you come

to the station and camp in the yard." No attempt at a bribe. Thoroughly

impressed I gave them $5 for "tea". Word spread quickly about

my exploits, "The mzungu was afraid to sleep in town so he slept

in the bush!" The other thing about Africa is that people are unafraid

to laugh at you - in front of you. Surrounded by twenty laughing cops

I had to join in - I returned to the border in style with an official

escort of three soldiers. My departure from Zambia was painless,

quick, efficient. Despite the potholes and the nights in the truck I

had fond memories of Zambia. I entered Tanzania. I entered a paradox. Immigration

required $50US cash for a visa - and no they didn't take travellers cheques.

I was stumped. The clerk generously gave me a seven day pass and told

me to pay at headquarters in Dar when I got more money - in retrospect

it would have been kinder if he had reached over the counter, slapped

me, and sent me 200km back into Zambia to the nearest bank. I moved over

to Customs, was ignored for 15min, filled out a form in quadruplicate,

signed and stamped by another clerk, in to see the "boss"... "So

tell me, how is the Microsoft case proceeding." I thought I was

finished - had to pay road tax, another form � another shack, another

clerk copied information from my papers to a ledger - another shack,

another clerk copied information from my papers to yet another ledger

- back to Customs to drop off the duplicates� and I could go. At

2 hours, it was my longest tangle with African bureaucracy - it was only

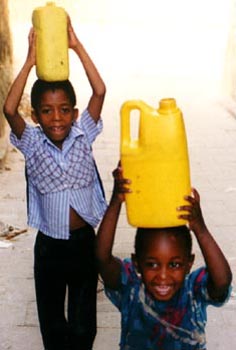

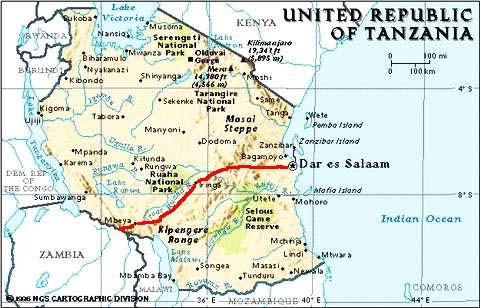

a warm up... One thousand kilometres cutting across

the waist of Africa with little sleep and precious few reserves of strength.

Long stretch to Iringa through mud hut towns with metal roofs touching,

decrepit mini-bus taxis hooting into crowds penned by tea shacks, darting

traffic. Cool afternoon air, belligerent bursts of rain, elephant grass

higher than the windshield, black tea at an Agip gas station kiosk looking

mournfully at the "very soon to be working" cappuccino machine. Darkness. I descend an escarpment

suddenly, corkscrewing down, slaughtering thousands of flying vermin,

the air turned tepid then musky. Stanley�s Hella high beams cut

holes through the jungle tunnel. Two lionesses feasting on an antelope

road kill spun around in the headlights and slunk off the road. I

blinked, the whole scene was surreal. Tea in a scrap board trucker stop

in Morogoro. Speeding ticket?! from a speed trap - the old twisty corner

50km temporary village slowdown ambush. Don't mind paying for "tea" but

a $10 ticket burns me! 50 clicks out of Dar the road turns nasty, and

I�m beaten up for the last hour. Arrived 1am, tired, hungry, lost � there

are precious few street signs in Dar. An attendant at a BP station

offered to guide me to a hotel and confided during the ride that it was

his first time to ride in a Land Rover. Paid $60 for one night

in a "Business Hotel" � filthy room, the shower head shot directly

onto the bathroom floor, remnants of the last tenant's dinner. I was

so tired I had to watch � an hour of World Match Play darts in order

to sleep. Desolation

in the Capital Tanzania is a very large country,

945,087 sq km, with a population over 30 million. The country is a paradox

in many ways. It was one of the purest attempts at African socialism,

the president Nyerere believed deeply in an agricultural economy and

made several attempts at it - unfortunately the country inherited the

bureaucracy and corruption that comes along with socialist central planning.

Tanzania can claim the credit for ridding Uganda of the infamous Idi

Amin. After Amin invaded their northern border the cash strapped country

scraped together an expeditionary force and routed "Africa's best

equipped, best trained army at the time", marching right into the

capital Kampala. Unfortunately they received no foreign assistance and

this $500million adventure further decimated the government�s coffers.

With the fall of communism, aid donors were no longer prepared to bail

out the economy in the face of widespread corruption "which just

about matched the amount of aid that was flowing into the country".

Multi-party elections were held, ministers were replaced, corruption

began to be addressed. Having complied with the "free

elections" and "freedom of the press", Tanzania is now

suffering through "controlled domestic spending". To put this

in perspective - it spends over 50% of it's annual budget on foreign

debt interest! There is over 80% unemployment in the major cities. Sitting

near the epicentre of the AIDS pandemic with a highly infected population

- it has less than $100 budgeted annually per person for health, which

is not even enough for an AIDS test - never mind treatment. There are

no bank machines in Dar. There are no supermarkets. I bought my own oil

for an oil change at the Land Rover dealer. The city huddles around the

flickers of foreign expenditures scattered here and there. Far from the "civilization" that

I had anticipated, Dar prolonged my labours in the margin. One travel

agency in town will issue travellers cheques - and one other exchange

bureau will exchange them for shillings - which can be converted into

US dollars � which can then be taken to Immigration to pay for the visa. But

what should have been a 10 minute process consumed two days! Mind numbing

lines, heedless clerks, endless duplication of paperwork - I was taxed

to my limit. My comrade in suffering was Samuel - a quiet Somali refugee

who was applying for a visa for his sister and had been queued quietly

in the suffocating hall for two weeks.... waiting. We joked, he told

me which clerks were best, and lent me his pen when I forgot the cardinal

rule of African bureaucracy - always bring a pen! I gratefully accepted

my stamped passport after the second day of sitting and sweating, and

waved to Samuel as I made my escape. Gem

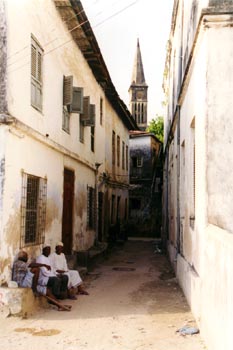

of Africa - Zanzibar On one of my last nights after a

nice meal, the rain suddenly rolled in. Cool wind and then gusts of water

pressing down, stripping the heat from the sky. The ancient House of

Wonders shuddered beside the gleaming Arab fort, screened by palm trees.

Dhows bobbed on their liquid tethers and the tide nipped at the edges

of the pier. Vendors galped and laughed, berating assistants to hold

large plastic sheets over their wobbly kitchens. Tourists ducked into

their pools of light and departed with softly steaming morsels. And then

the clouds passed away and the night sky showed off a million diamond

drops glittering on the windows and laughing children. Lovers walked

by wrapped in their sentiments. Sitting at the edge of the ocean I felt

that I'd regained the center of things. Late tonight I pick up John Hiscock

and Alex Semple - my partners for a further exploration of Zanzibar,

ascent of Kilimanjaro, and discovery of Serengeti and Ngorongoro. My

solo tour is over for now - probably a good thing, I'm afraid I will

talk their ears off after so much silence. I hope this finds you well. |

All rights reserved

Struggling

through Tanzania

Struggling

through Tanzania